00:00:05.839

Hey everyone, I'm so glad to be here. So many folks know me, but for everyone I haven't had the chance to meet yet, my name is Kerri Miller. I have the immense privilege to talk to you today about mistakes.

00:00:12.780

I'm going to share a few historical blunders, along with some modern head-scratchers, discussing the challenges and opportunities they present. But mostly, I want to tell you a few stories of failures that I carry around in the back of my mind as I go about my day as a back-end engineer at GitLab, specifically on the code review team, where we deal with everything related to code reviews and merge requests.

00:00:30.900

Beyond my day job, I'm also a gamer. I used to be a marionette puppeteer, a glass worker, and a professional poker player. Additionally, I'm a long-distance endurance motorcyclist, and this summer, I'm attempting to ride through all 48 contiguous states of the United States in 10 days or less. It could turn into a disaster; who knows? But I'm eager to make the attempt.

00:01:01.820

Now, enough about how cool I am, trying to seem relatable and human. Let's get into the topic here. I want to share with you a story about a time when I wasn't so cool. Surprisingly, I never thought I would become a computer programmer, despite the fact that I was privileged to grow up in a household where a computer was readily available to me. Instead, I thought I would be an artist. I struggled with math and, when I started college, pursued a performance production degree focusing on lighting and set design, with a minor in puppetry.

00:01:30.900

I especially loved working on Shakespearean performances. One summer, I was fortunate enough to work as a crew and cast member in a small company performing three different plays by Shakespeare at various venues around town. One night, I strode onto the stage and proudly spoke the lines: "Gracious, my lord, I should report that which I say I saw, but I know not how to do it." The other actor looked at me, and I looked at him; it was clear he had forgotten his lines, prompting me to continue.

00:02:05.280

Despite this, I pressed on, determined to make my mark. I recited, "As I could stand my watch upon the hill, I looked toward Burnham and an on, and thought the woods began to move." This was crucial information for the messenger to convey to Macbeth because he was prophesied to be king until Burnham Wood came to Dunsinane. Unfortunately, I was in a production of Henry V, not Macbeth.

00:02:35.400

I could have covered it by delivering a clever line like, "Oh, my lord, thou care not for that trifling news; let us discuss the real thing." But instead, I panicked and said something ridiculous. This led me to embrace the idea that sometimes mistakes happen, and whatever they say about never being the crime but the cover-up, I certainly nailed it that night. It's one reason I collect stories about mistakes and disasters.

00:03:07.140

Now, speaking of disasters, I really don't want to talk about 2020. I spent most of that year at home, reflecting on my local surroundings and reading deeply about the early Roman Empire and the Bronze Age collapse. I even ventured further back to the earliest empires in the Western world, and that's where I discovered the story of someone named Kush, and I want to introduce you to him today.

00:03:39.960

This three-inch square clay tablet was made around 3100 BCE and recently sold at auction for $230,000. It features engraved Sumerian pictographic script that predates even cuneiform. This tablet was kept in the temple of Inanna in Uruk, which is in southern Iraq. It is one of 77 pictographic tablets that we can tell were written by the same individual whose handwriting is on this tablet. His name is Kush.

00:04:10.440

Kush is distinguished as the first person in history whose name we know. His name consists of two pictograms: the lowercase 'i' shape is for 'ku,' and the fuzzy vase represents 'shin.' Historians are confident in identifying this as his name because it appears on 17 tablets, often accompanied by the title of 'Sangha,' which means head priest or functionary—a kind of middle manager of a temple.

00:04:27.300

Now, what was he recording on this tablet? The tablets don't always follow a top-to-bottom or left-to-right arrangement, so you may have to tilt your head to see this better. There are three symbols on this tablet. The top one is the symbol for barley, the middle one represents a brick building with a chimney, believed to be a brewery, and the bottom symbol is a combination of the barley pictograph and a symbol for exchange or trade. On this tablet, Kush is tracking having received a shipment of barley at the brewery.

00:05:01.740

This set of symbols represents a time period of 37 months. The Sumerians used a 12-month lunar calendar necessitating a leap month every three years to synchronize with the solar year. From this, we deduce that Kush's tablet tracks a period of three full modern solar years. How much barley are we talking about? This is a tricky question because the Sumerians used a combination of base-6, base-10, and base-12 numbering systems, and the size of the marks matters as well.

00:05:33.600

After doing the necessary calculations using their base unit of measurement, which is a vessel of about five liters in capacity, we find that Kush's records indicate 135,000 liters of barley. Here's another tablet believed to be a cheat sheet of sorts, created by Kush. In the middle column, we have deciphered a series of equations revealed the amount of barley and malt needed for brewing different-sized batches of beer. In the upper left-hand corner, we find a basic multiplication table of serving sizes.

00:06:10.620

To read this, you need to know that a dot equals 10 units, and fractions are represented by grouping bowls together; the number of bowls in the group serves as the denominator of the fraction. For instance, in this row, 20 quarter units will equate to five units since an elongated bowl on its side represents 5.

00:06:45.420

Here's another example: one third translates to three and one third. You're following along great! We also have a sideways bowl, which indicates five times one-half, resulting in five. However, Kush made a mistake; he accidentally put a five where he should have placed a ten. This was a mistake because we have other copies of the same information on different tablets also written by Kush, and those tablets do not contain this error.

00:07:19.620

So, poor Kush. While he is the first person whose name we know, he is also the first person recorded to have made a math mistake, bearing the blame for this incident. But that's not the end of typos in history. Have you ever heard of the so-called Wicked Bible, also known as the Sinners Bible? This version of the King James Bible, published in 1631, was well-received, yet there was one critical error: in the Ten Commandments, it stated, 'Thou shalt commit adultery.'

00:07:43.620

King Charles I was not amused by this, nor was the Archbishop of Canterbury, who famously remarked that, back in his day, people cared about details, unlike the kids today. The printers faced severe consequences and were ultimately found guilty of blasphemy by the Star Chamber—allegedly a sin against the church. They were fined 300 pounds and lost their license to print books entirely.

00:08:10.740

No one knows exactly how many copies of the Wicked Bible were made, but many were destroyed once the error was discovered. Surprisingly, 15 copies still exist, and if you happen to have $100,000 lying around, there's one for sale right now on AbeBooks, a pretty good price, considering its historical significance.

00:08:44.700

What I want to emphasize here is that we humans are storytellers. When discussing mistakes or successes, it's part of our nature to see ourselves as the central characters in the story. We often interpret events where we may only be minor players, believing the issues presented solely pertain to us. We might think we were only added to an issue or tagged in on Slack, and by the time we logged on, the problem was already resolved. Yet, we still want to take credit for the positive outcome.

00:09:00.120

Conversely, when discussing mistakes, we often downplay our involvement. We claim that the mistake was someone else's fault or we present ourselves as mere bystanders, at the mercy of the code. We all feel this pull since we're all human, and just like Kush, we make mistakes as well. However, we are not victims of software; we are its authors. We invented math and writing to tackle challenges our brains simply can't handle very effectively.

00:09:34.920

So, it comes as no surprise that many people find math, logic, and programming to be quite difficult to varying extents. Humans simply are not wired for it. The engineers who wrote the software that you may be cursing today are human, just like you and me, and we must give them credit for the challenges they faced at the moment.

00:10:02.480

If we choose to talk honestly about success and failure, we must recognize that software is essentially a compromise to address human problems. It often reflects the conclusion of arguments between what would be proactive and what is a pragmatic solution. Because it inherently can only cover a portion of the possibilities with which it will operate, it is inevitable that software will eventually fail us.

00:10:32.640

So where do we find the strength and resilience, the bravery to continue striving toward finding resolutions when we know we are doomed to fail? Once you accept that you cannot know everything, it’s a short step to begin to question how much you can actually know at all, especially considering that we can't even define the limits of knowledge itself.

00:10:57.420

It's a cliché, I know, but looking back and wishing we had known then what we know now is a common sentiment. Often, only in retrospect can we fully appreciate the value of the knowledge we've gained. A few years ago, when I asked people what they wished they had known about programming before starting out, almost every single person said that software was all about people.

00:11:23.460

Seldom will you ever be truly on your own; there’s always a team of people contributing to the success of a project. Thus, communicating intent and developing empathy to understand the perspectives of others allows you to multiply the efforts of everyone around you. Learning to work with others in a constructive, positive manner brings out the best in those around you, which is a skill worth having.

00:11:49.080

Tech is a team sport, but while we multiply the successes of those around us, we also run the risk of compounding and amplifying the effects of small individual mistakes. A series of small individual mistakes culminated in the story of the Vasa ship in 1628. It is a well-known engineering disaster, particularly among enthusiasts in engineering disaster circles.

00:12:07.680

In brief, Vasa was commissioned by the King of Sweden, Gustafus Adolphus, in 1625 as part of Sweden flexing its military muscle against Poland and Lithuania. The ship was built by a private corporation using both public employees and contractors and was lavishly decorated. It symbolized the ambitions of the King and Sweden, representing one of the most powerfully armed vessels in the world at its launch.

00:12:39.600

Henrik Hybertson, the shipwright, had signed a contract to build four ships and began construction using the same designs he had applied to other vessels in both Sweden and his native Holland. The principles of shipbuilding at the time were not formalized, and there were no textbooks or guidelines available to reference. Ships were individual creations built by master craftsmen, with variation between them a common feature.

00:13:12.060

Henrik Hybertson had a reputation for constructing stable, fast vessels. However, after losing ten ships in a naval skirmish in 1625, the king demanded that the plans for a new, larger vessel be changed. Initially, Hybertson resisted, but he fell seriously ill later in the year and had to retire from shipbuilding. He handed the entire project over to another Dutch shipwright whose name also happened to be Henrik.

00:13:43.620

Henrik the Younger had no qualms about following the suggestions coming from the King. Even if he couldn't make the ship longer, he decided to model it after a different ship that had already been laid down. This other ship featured two gun decks, allowing them to carry twice as many cannons, and he also added tonnes of ornamentation to make it even grander.

00:14:06.660

On August 10, 1628, the ship was completed, and thousands gathered on the shore to watch its launch. The day was fine, the weather clear, and there was only a slight breeze from the southwest. As the ship was taken out to the harbor, its sails were set, and it began moving eastward. They opened the gunports and rolled the cannons out to fire a salute to Stockholm as they departed.

00:14:45.240

However, as it passed a series of bluffs south of the harbor, a gust of wind filled the sails, causing the ship to heel over to port. The crew lowered the sails, and the ship slowly righted itself as the gust passed. A short while later, a stronger gust of wind forced the ship over to the port side again, pushing the open lower gunports below the waterline.

00:15:16.920

This disastrous turn allowed water to flood into the lower gun deck, and the ship couldn't right itself quickly enough, taking on water at a truly alarming rate. It sank rapidly, just a mile from where it had departed, with 30 sailors losing their lives as they were unable to escape.

00:15:43.620

As the King was engaged in military activities against Poland, news of the sinking took weeks to reach him. When he finally did, he was furious and demanded that someone be held accountable. The captain and crew were interrogated about their conduct during the ordeal, and significant focus was placed on whether the gunports had been closed and the cannons secured.

00:16:14.760

However, the captain and crew shifted blame towards the shipbuilders, questioning why the ship was designed to be so tall and narrow. A taller ship would be susceptible to tipping and would struggle to right itself quickly—something that had been demonstrated in early trials while the ship was still docked. Yet, no one was willing to admit that years of effort had to be discarded to delay the delivery of Vasa to the Navy.

00:16:41.760

With no guilty party to blame, fingers were pointed at Henrik the Elder, who had conveniently passed away due to the illness. It turned out he had been the initial designer, but Henrik the Younger had made modifications during the building process, resulting in the ship's poor design.

00:17:09.800

When the shipwreck was rediscovered in the 1950s after being submerged for nearly 300 years, modern principles of shipbuilding were applied, revealing that Vasa's height from the keel to the top was excessive—as earlier tests had indicated. Additionally, the fact that the gunports had been left open further contributed to the vessel taking on water.

00:17:44.400

This combination of minor mistakes led to a disaster. The story of Vasa serves as a reminder that changing specifications and designs can lead to tumultuous outcomes—especially in toxic cultures where honest communication is ignored in favor of deadlines imposed by executives far removed from day-to-day operations.

00:18:05.940

However, not every failure is easily classified as a mistake. Some ideas may be too ahead of their time or simply lack enough immediate benefit to warrant adoption. For instance, attempts to implement a base-8 numbering system encountered resistance, as did Kodak's internal use of a 13-month metric calendar for decades. Both ideas had clear advantages, yet it wasn’t enough to convince a broader audience.

00:18:46.220

Consequently, labeling something a mistake or disaster often boils down to a matter of perspective and interpretation. Adopting new ideas that significantly challenge existing paradigms proves difficult, particularly in human systems. Our base-12 system, used by Sumerians, likely evolved from counting patterns based on our anatomy—counting our knuckles and fingers.

00:19:14.800

While both the base-10 and base-12 systems are perfectly viable within their respective cultures, when we step outside these frameworks, like base-7 for instance, it feels unnatural. Our brains aren’t accustomed to processing data along those lines. We also examine fundamental limitations of memory's capacity to hold discrete items, typically seeing seven as the optimum amount of distinct data we can keep track of.

00:19:41.160

With software design, we don’t want to overwhelm users with too many options and must consider fundamental principles of human behavior. A few years ago, Revlon, the cosmetics company, decided to acquire a rival firm. To fund this acquisition, they engaged in a complex series of financial maneuvers, borrowing billions of dollars.

00:20:05.520

This led them to hire Citibank as their loan servicing agent, essentially acting as the point of contact for both lenders and borrowers. Revlon's situation became dire; their liquidity was extremely tight. It came down to two outcomes: they could either find a groundbreaking way to generate cash quickly, or they could sell off portions of the company to repay debts.

00:20:32.220

As Revlon scrambled to buy time, they produced increasingly convoluted debt restructuring deals. In this game of high finance, lenders not included in the deals were left frustrated, receiving only partial interest payments. In a moment of sheer blunder, Citibank mistakenly sent Revlon's lenders a staggering $900 million instead of an $8 million interest payment.

00:21:03.420

Initially, the lenders believed this was a potential sign that Revlon had more funds than previously thought. However, Citibank's subsequent frantic messages indicating that the wire transfer was an error didn't change their minds. Therefore, in the ensuing court case, the lenders argued they had a legal right to keep the money.

00:21:24.080

The court ruled that Citibank had conducted the transaction with a flawed process that allowed the error to occur. It stemmed from a mere oversight—a checkbox that should have limited payments to $8 million but had only marked off the principal. Thus, Citibank inadvertently became the unintended, unplanned owner of almost a billion dollars worth of Revlon's debt.

00:21:50.440

This incident serves as a reminder of how tiny mistakes can lead to extraordinary outcomes. As with all talks on mistakes, we often see them as opportunities to learn. One of my favorite examples of this conversion of mistakes to innovation is Play-Doh.

00:22:07.360

Originally invented by a chemist while attempting to create a new wallpaper cleaner, it led me to question whether one could clean wallpaper in the first place! Taking a broader perspective, we exist along a long continuum of human-created mistakes, errors, and various failures from which we all can learn.

00:22:38.440

Hard problems are difficult not because of the effort required, but because of the costs associated with errors. For instance, in an ongoing conversation on social media, some debated returning to traditional waterfall development methods, suggesting that detailed planning upfront diminishes failure chances.

00:23:08.440

Unfortunately, predicting everything that could go wrong in a project is nearly impossible! Some pitfalls are straightforward based on prior experience. If I touch a hot stove and burn myself, I learn not to touch it again. Empathy also plays a key role; if I witness someone else get hurt by it, I can circumvent the harm—thus learning from their experience.

00:23:35.200

Yet, when confronted with potential risks for which we have no direct experience, we rely on imagination—an avenue where we inevitably think, "It won't happen to me; I'm special." This mindset can lead to unexpected failures. Take, for instance, common safety standards, or even when people believe machinery isn't in gear.

00:24:07.560

Such misperceptions often culminate in surprising failures in complex systems we commonly work with. Furthermore, there are scenarios we might remain blind to precisely because they are outside our realm of experience—fires, earthquakes, and even unexpected remote work circumstances.

00:24:39.360

However, everything becomes more complicated when we consider failures that defy categorization. We must delve into history and the connected stories of bygone disasters across other industries and timelines. Returning to ancient Rome, we often envision a city characterized by magnificent architecture, golden statues, and gleaming marble. Yet, most of Rome during the Empire was made up of functional buildings constructed of brick and fired clay.

00:25:24.280

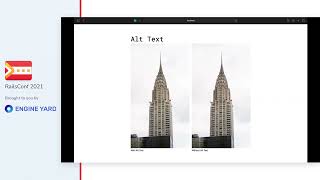

This photograph shows a Roman apartment building built in the late 2nd century CE. It's still standing after nearly 2000 years. This is how Rome would have looked as you walked down the street, embodied in the Trajan Market, built around the mid-first century CE. The Imperial Roman style of building, termed opus caementicium, which translates to 'brickwork,' relies on a remarkable invention known as concrete.

00:26:01.640

Remarkably, thousands of years later, we have yet to develop anything superior. The Roman Empire displayed a considerable demand for concrete, bricks, and tiles, including their hypocaust systems used in underfloor heating as well as pools and bathing facilities. To satisfy the Roman desire for such commodities, brick and tile production initiated the start of large-scale communal industries.

00:26:47.440

In the past, brick and tile makers were compensated for productivity; they were paid for each brick or tile produced rather than for hours spent in a factory. This means individual craftsmen created their goods, marking them as their own with a maker's mark. This symbol often took the shape of a swirl made with their fingers or a pattern, but literate artisans might mark their clay with their names or lot numbers.

00:27:24.720

Some artisans even designed stamps to identify their products. However, archaeologists have unearthed countless tiles and bricks featuring backwards stamps, often assumed to be the work of a literate person who didn’t realize their work would later be stamped or an illiterate craftsman who was unaware the letters needed reversing. Yet, is this truly a 'mistake'?

00:28:05.240

That mark still identifies the craftsman, regardless of its orientation. Countless tiles bearing the footprints of cats, dogs, sheep, goats, deer, and even pigs serve as evidence that the ancient world was littered with everyday interactions—indeed, cats played a significant role in controlling rodent populations. Archaeological findings include a fascinating array of human and animal footprints on tiles and bricks, with the significance of each showing our connection to a living world from long ago.

00:28:46.520

As it is often said, there are no new stories, only new characters and settings. Considering this, when we confront modernity through a postmodern lens, we recognize multiple references to history. We stand on the shoulders of giants, but it does not signal the end of our story—rather, we become temporary stewards of our craft.

00:29:25.960

Our expressions in code aim to resolve human-sized problems, recognizing that code evolves as a living entity. It's essential to grasp that no line exists in isolation; each call, each message, represents decisions made by someone who followed a diverse, rich path to produce that specific piece of code.

00:30:07.340

This engagement forces us to observe pixels and understand variables while also acknowledging the broader narrative of our software and its functionality. Our stories define who we are. Recognizing your story expands your worldview, and once you understand what your story is, you can transform it. We are merely links in a long chain of humanity, marked by our successes and failures.

00:30:43.520

I find relief in understanding that I'm akin to all the links that came before and those who will follow. I endeavor to be as strong as I can and support the collective chain, even though we all inevitably fail at times. Reflecting on our history brings a sense of comfort, while also acknowledging we no longer operate on the same paradigms as in the 1990s or beyond. Recognizing that early engineers grappled with similar issues to ours today can offer perspective.

00:31:17.040

Reviewing documentation from the past reveals discussions on cap theorem, object orientation, and database robustness. Those pioneers dealt with the complexities that drive our propensity for failure just as we do today. Humans relate to the world through stories, and through code, we possess the means to articulate and relay that story timelessly.

00:31:31.920

Therefore, we must seek lessons from every corner of human experience to better understand how our pursuits can succeed and fail. That's why I continue to advocate for the need for storytellers and fewer emphasis on mere facts. I want to embrace more sonnets and less dictionaries. It is essential to cultivate a richer narrative around ourselves and our code, finding stories worth living.

00:31:49.100

Thank you so much for joining me today. I am Kerri Miller, and you can find me everywhere online at @carrizor. Thank you for listening to my talk on mistakes! I hope it resonates with you.