00:00:00

I always forget something. Okay, I'm ready.

00:00:13

Are you ready? Great. All my talks start with a content warning. That's two for you and one for me. The two for you are that this talk involves a discussion of terminal illness and death, along with the emotions that surround those topics, specifically loneliness and guilt, through the lens of end-of-life care. If that subject feels heavy for you and you need to step out, I totally get it. You will not offend me, and it will not hurt my feelings if you need to give yourself a bit of emotional distance. You could look at your phone, jot in a notebook, or cross-stitch. I'm totally into it. I've been there too. The second content warning for you is that I do have two videos in this talk. One of them has audio, it is captioned, and it's kind of dark for lots of reasons, but it's there. If something goes wrong with the video, the captions can help us with the content. The second video later doesn't have audio, but if you experience any kind of motion-related nausea or discomfort, I'll give you a heads-up before those videos start. They are only about 30 seconds each, and I'll be talking through them as well. The content warning for me is please don't fall off the stage. I pace when I talk; it's how I deal with the anxiety of being on stage. So if you see me getting perilously close to the edge, just throw your arms out and say, 'No, Jeremy!' Okay? So please take care of yourself. Do what you need to do. I want you to be safe, I want you to get something out of this, and I want us to be here together. Cool?

00:02:00

Let's start with some thank yous. First and foremost to Brenna, who's sitting here in the front row. I'm going to talk about her a lot. Thank you, Bren, for so many things, and thank you to the organizers. Conferences are really hard. Bren and I, along with a couple of other folks, organized a conference in Seattle, so we get how hard this is, and they've done an amazing job. Again, thank you to all of you who have stuck through and come to this final session.

00:02:34

I want to tell you a story. I took this photo in July in Bermuda while I was with Brenna, and I want to explain how we got there. We were in Bermuda to fulfill Barbara's last wishes, which was to have her ashes spread in Bermuda, where she had lived most of her adult life. So I'm here to share that story about my family, essentially about making things that matter about holiday gifts. I'm going to tell you a story about fighting when you're going to lose — there's no other option; you are going to lose. I also want to tell you a story about a five-dollar computer, which is my prop for this talk, but I left it in my backpack.

00:03:30

Before we get going, I want to talk about a word. I have a speech impediment, which is why I started public speaking. So when you hear me stutter on words, it's a combination of nerves and a physiological impairment. This word is really hard for me, and it's important in this discussion. That consonant with that hard 'I' after it messes me up every time. So saying it the first time is the hardest; it's like a roadblock I have to figure out how to get around. I’m going to count to three, and I need us all to say it together; that’ll help me. Okay? So, one, two, three: 'dignity.' There it is! We're going to talk about this word a lot.

00:04:01

Here's the agenda. Well, actually, I don't have a structured agenda; I will just ramble. We're going to meet some people, we're going to talk about loneliness and guilt. We’ll be experiencing loneliness and guilt through the lens of caring for someone who is terminally ill. We're going to discuss the difference between soothing and solving, how to build the right thing, and more specifically, how to know what to build when it's time to do so. We'll discuss measuring the impact of what you build and close with a short discussion on what to do when you lose the fight.

00:04:42

Let’s meet some people. First, there's me. My name is Jeremy; you know that. You probably saw it on a website. I'm a programmer and a teacher. I live in Seattle. I really like tattoos and records, and if you want to come talk to me later, I'm always eager to discuss tattoos and records. I help run a little conference you probably haven't heard of, or if you're part of this crowd, you might have. It’s called Open Source and Feelings, and it's exactly what it says on the tin. I'm the least important person in this story; I'm just the person privileged enough to tell it.

00:05:21

This is Bren. She's more important. She's a software engineer, specializing in build and delivery engineering. She's a crafter, a runner, and a gamer. Most importantly, she is the kindest person I’ve ever known. She's also my girlfriend, partner, and best friend. We've been living, laughing, and loving together for four years and counting. She's here today in New Orleans — she's sitting in the front row. Hi, Bren! Bren deserves a round of applause.

00:06:01

This is Barbara, Bren's grandmother. She passed away in May but remains the most important person in this story. She is our central character. This is where our first video is. It's awkward for me to be the one telling Barbara’s story when her relationship with Bren is obviously much stronger and more significant. When we talked about this, we wanted to give Bren a voice in this presentation, so we settled on a video to do so.

00:06:16

This is Bren talking about what made Barbara such a special person. When we tested this earlier, we had to really crank the audio up, so let's prepare. It's about 30 seconds long, let's see if it works.

00:06:40

She was an amazingly intelligent woman. Barbara was independent and headstrong; I would describe her as a badass. I don't know if that's a common trait of grandmothers, but I want to believe it is. It's a shame that video was so dark because in Bren's lap is our adorable chihuahua, Rosa. That was my opportunity to share her with you, so if you want to see pictures of Rosa later, please come and do that.

00:07:15

Barbara was a badass, and it’s worth discussing her story. She was born and raised in the eastern United States. On the playground, she spent most of her days. I’m not going to do that to you — she grew up in New Jersey and emigrated to Bermuda in the 1960s after a bitter divorce. The thing that drove her away was her desire to have her own career and to be in charge of her own destiny, something that her ex-husband and, frankly, the rest of her family adamantly opposed. She lived and worked in Bermuda until her retirement in 1991, primarily in the banking and hospitality industries. She earned the title of manager, which is amazing.

00:08:16

A few years after emigrating, she was joined in Bermuda by her daughter, and Bren was born sometime after that. Bren describes Barbara as her role model, tireless cheerleader, best friend, and second mom. Barbara instilled in Bren that success and empathy are not exclusive concepts and that she could achieve anything she desired with hard work, dedication, kindness, and perseverance. It was Barbara's career working with computers and managing teams of men that inspired Bren to go into engineering herself.

00:08:35

Bren eventually emigrated to the United States and settled in Seattle, which worked out really well for me. After retiring, Barbara followed Bren to Seattle as she needed more help with day-to-day living. Bren arranged for her to settle in an assisted living facility, and they began this routine of daily phone calls and visits.

00:09:15

These women, these amazingly strong women, followed each other across continents and decades, each supporting each other as the situation demanded, each determined to be there for the other. On December 12, 2012, Barbara suffered a series of ischemic strokes. This occurs when a blood clot somewhere in the body, usually in the leg, separates and travels through the circulatory system, landing in the brain. The result was a complete loss of her ability to speak, along with a complete loss of sensation and control on the right side of her body, leaving her bed-bound.

00:10:05

She could sit in a wheelchair but didn't have the strength to move it herself, so she was really spending most of her time in bed. She lost her independence essentially overnight. After her stroke, Barbara needed 24-hour care, so Bren arranged for her to enter a facility that could provide that care, a nursing home. That's where Barbara lived for four and a half years.

00:10:54

Bren visited Barbara, and those visits were hard. Some days, the connection between brain and body was strong enough that Barbara could speak a little and was with Bren. It felt a bit like old times; they could talk, laugh, and catch up. Often, Barbara was frustrated and angry at her inability to get her body to cooperate and vocalize the things she was thinking and feeling. They made it work, developing a surprisingly elaborate system of gestures and pointed looks, communicating volumes with just their expressions. It’s the kind of communication you have to grow up with someone to have.

00:11:41

Some visits were really bad. About once a month, or maybe once a quarter, Bren would find Barbara agitated and confused. She would have woken up, forgetting why she was there, where she was, why she couldn't move, and why she couldn't speak. She was terrified and lost. It wasn't until Bren arrived that she would calm down. Bren had the unfortunate job of explaining to Barbara what had happened, where she was, why she was there, and how long it had been. Bren never sugar-coated. She always told her the truth, which I immensely respect.

00:12:14

Well, it wasn't to hurt her or scare her; it was to be honest and whole with the person she loved most. But it felt like picking a scab. Once I entered the picture, I began visiting as well. I typically visited once a week, for about an hour or maybe two. Over time, a pattern emerged; we are creatures of habit. My special skill is making really good coffee. If you want to be my friend, if you want to live in Seattle, if you want to come to brunch, I make great coffee. Bren is an accomplished baker, so we made coffee, put it in her special china that we rescued from storage, and brought her scones or maybe a pie, as she really liked pie.

00:13:35

We would sit and talk about the weather and anything to engage her and draw her out to make her feel connected to us. Eventually, we would pull out our phones to show her photos. It was the best we could do to give her a sense of what our lives were like — what our bus rides looked like, what our office looked like, what our home looked like. We got into the habit of taking more pictures just so we'd have something to share with her when we visited. Bren was also good at talking with Barbara, asking her questions to draw her out. Typically, these were yes/no questions because that was what Barbara could manage most of the time, but I always respected that effort; it’s hard.

00:14:53

After about an hour, we’d clean up, give her a hug, tell her we loved her, and say goodbye. In doing research for this talk, I found many stories like Bren and Barbara's, but one stood out to me. Dr. Ranjana Srivastava wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine about a friend who suffered a stroke similar to Barbara's. After the stroke, Dr. Srivastava started keeping a journal in which they described both the objective observations of their friend’s decline and eventual death and the subjective experience of watching someone you care about die. This quote resonated with me because it captured the moments when I couldn’t handle the weight of the visit.

00:15:55

I felt the frustration and difficulty, so I pulled out my phone and read Twitter for a couple of minutes. I think we’ve all been there, perhaps not quite so dramatically. Dr. Srivastava also said it is something impossible to watch someone you care about slowly lose their connection to what makes them human. It’s something else entirely to watch someone you love go through that, and that is what I want to discuss. It seems unkind to leave but painful to stay. Strokes are cruel; they rob us of our essential humanity and dignity as people. They take away our agency and control over our environment and impose an impossible burden on our loved ones.

00:16:57

On Barbara's side is monotony, loss of agency, disconnection, and a widening gulf between her and the rest of the world. On Bren's side is the unshakable feeling that she can't do enough for Barbara, that there is always something more she should be doing; it's a feeling of frustration or boredom during a visit and then being really angry at herself for feeling that. It creates a spiral. The connecting emotion here is isolation — loneliness on Barbara's side due to this literal disconnection, and on Bren's side feeling alone in managing this impossible situation.

00:17:46

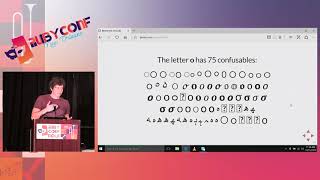

More research: this is the last research I promise. Dr. Lee Atronach, writing for The Huffington Post, discussed loneliness. Dr. Gu Neck is a psychologist who studies the physiological effects of grief, and in this article, which I provided a bitly link for, they recount a study that reviewed about 40 years worth of research on loneliness. It was titled 'Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality,' published in March of 2015 in Perspectives in Psychological Medicine. Let's talk about this study a bit.

00:18:38

This was a review of academic research on loneliness, and after controlling for all possible confounds, Dr. Gu Neck showed that social isolation, measured through various means, corresponded to about a 30% increase in your likelihood of mortality. Put simply, you’re much more likely to die if you’re lonely. Loneliness can be a confounding factor for which you cannot control. Dr. Gu Neck highlights three remarkable aspects of this study. First is the scope: this is a review of a large body of work across 70 scientific publications covering about three million participants across decades.

00:19:28

Secondly, young people are likely affected more — they are more at risk of increased mortality due to loneliness. Here, 'young' is defined as 65 and under. Most of us fall into that category. The real meat of the finding discovered no significant differences between measures of objective and subjective social isolation. What does that mean? It means that feeling lonely and feeling isolated are equally dangerous to your health as being objectively observed as lonely. I don't know how you objectively observe someone as lonely; that just sounds mean, but as someone who's felt lonely, I know what that feels like.

00:20:05

Realizing there is this demonstrable risk related to loneliness left me feeling like I need to do something. Loneliness and isolation can kill you. Bren fretted about being away from Barbara, not just because of medical concerns — 'Is she healthy? Is she okay?' — but because of the implications of loneliness and isolation. She feared losing what remained of Barbara over time. Additionally, Bren struggled to get through each day, and we began to feel a heavy gloom in our visits, like we were waiting in purgatory for the inevitable. I was frustrated because I couldn’t fix this. As an engineer, I want to solve problems, document them, test them, fix them, and publish that solution so no one else has to go through this ever again.

00:20:55

But I couldn't. All I could do was make it a little bit better. I didn't know how, but I had been thinking about it for a long time, and I observed something that eventually became an idea. I want to walk you through my thought process because all my ideas begin the same way. Imagine I'm at lunch — that's not hard to imagine. Picture me having a taco at lunch; it’s an excellent taco, beautiful, and perfect. This taco is the prototypical taco by which all other tacos must be judged. I want to tell Bren about this taco, and she'd be mad at me if I didn’t share it. So what do I do? This is the audience-participation part: what do I do?

00:21:46

I pull out my phone, take a picture, and digitize my taco. Through the magic of the internet, I send it to Bren, and a few seconds later, she is ecstatic that I've shared the perfect taco with her. That’s me — that’s us. That’s how we do it in 2017! That's how my family communicates. We text; we don’t Facebook, and none of us have figured out how Snapchat works. We text, and the fact that this device can make phone calls is incidental. It could even be removed from the device and I wouldn’t know.

00:22:27

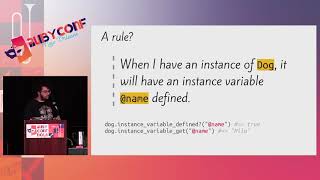

That raises an important question: how does this help Barbara? What if Barbara could get our texts? What if she could be a part of our conversation? That was it! What if there was a way for Barbara to be added to these conversations? For her to consume this stream of information we share every day? What if I could tag her in conversations just like I would anyone else in the family? My mind raced with possibilities. I always tend to go overboard; I’m dramatic. My first thought was to build an Elixir Phoenix app, to put it in the cloud so it could handle a million concurrent connections. We have a really big family. Okay, so I’d use Electron and probably React because that’s the norm.

00:23:14

I wanted to build something that could be installed on every platform — I could even put it on our toaster! It’d be great. I thought about building a laser so powerful it could carve my taco texts into the face of the moon, so every time Barbara looked outside at night, she'd be reminded of us. Bolstered by these thoughts, but somewhat intimidated, I did what I always do: I turned to you, the Ruby community. I turned to friends, I turned to blog posts, and I turned to conference talks to help me understand how to turn this idea into something actionable.

00:23:46

This is what you advised: John Highland, an engineer at New Relic in Portland, is a wonderful person, and his advice applies to nearly everything. He says to just be boring. If you want to buy a car, just be boring; if you want a dog, just be boring. What it means is to be awesome by being boring: use tools you understand well that solve mundane problems, so you can focus on bringing value to your users. That’s marketing speak: bringing value to your users. But this really resonated with me for the first time — just be boring.

00:24:25

He also mentioned that I think about every single time I type 'rails new'. It clicked — if I’m building something for Bren's grandma, I may as well use my grandpa's framework. What he's highlighting is that Rails is a known quantity; it's well understood, documented, and stable. There's a big community to support me if I get stuck. So, I decided to use Ruby, and that informed many other choices for me. For example, Rails will likely output something RESTful, so I need a UI device that can consume a RESTful interface, and that's probably a browser.

00:25:11

If it’s a browser, I can build it with HTML, CSS, and JavaScript — all things I enjoy. So, I thought I’d put it somewhere with a runtime that Rails could be a part of; to DigitalOcean I went! That felt good; I knew how I was going to build it. What I didn’t know was how to make a text message show up in a browser. I had seen various marketing text messages with their origins landing in browsers, but I didn’t know how to achieve that. But I knew someone who did. I met Greg at Steel City Ruby in its first year; I helped organize that event.

00:25:58

Greg is a developer advocate at Twilio, a company specializing in telecom integration with modern applications. He has a clever dog that he taught to step on a button for a treat. He also has an interesting story: what else can I do with a dog that steps on buttons? He thought of hooking this button up to an Arduino with a webcam so that the webcam could send him a text. Now, his dog gets a treat for stepping on a button, and he gets an MMS text to his phone. I figured if Greg can teach his dog to do this, he can probably teach me too. He wrote a helpful article that laid down the foundation of what would eventually be my solution.

00:26:44

Now, I had a framework, and I knew what I was going to do. I was going to use tools I understood and focus on solving my problem. It turns out that MMS is just a data format, and as an engineer, making data formats communicate is kind of what I do. The third piece of this was understanding how to help Grandmom. I was getting lost in this engineering rabbit hole; how does this help her? I’m a front-end engineer, and I did user studies that are fun, especially when they involve someone you love.

00:27:33

Barbara had some challenges: she had limited mobility and, not only was her right side largely paralyzed, she also had trouble with dexterity in her other hand, making it hard for her to hold a device. Her short-term memory and some dementia made the learning curve impossibly steep. Barbara was largely disconnected from the world around her, and it was difficult to keep her interested or to hold her attention. She also had a lot of difficulty speaking, which is why many might think of using a voice-augmented UI like Alexa.

00:28:23

I thought of it as a potential solution, but I realized that voice UIs wouldn’t work for Barbara. There’s a whole segment of the population for whom voice UIs are not accessible, so I needed a different approach. Barbara had good vision for her age — actually better than mine, as I wear corrective lenses, and she did not. That was a plus. Additionally, she hated her television — particularly the network variety.

00:29:01

I don’t know how much time you’ve spent in American hospitals, but there tend to be a lot of TVs, and they always seem to be tuned to a news channel. That can make a bad situation so much worse. Since Barbara hated her television, I planned to replace it with something better. That’s when I decided to use a Raspberry Pi Zero, which is like a little cousin of the Raspberry Pi. It’s a five-dollar computer with a one gigahertz single-core processor, 512 megabytes of RAM, two micro USB connections, and mini HDMI — five bucks! It has more processing power than the laptop I brought to college.

00:29:55

With just a little bit of tweaking, it can run a browser. The new model, the Model B, even boasts Wi-Fi and Bluetooth right onboard, making it ideal for Internet of Things (IoT) applications, which fit what I wanted to build. My goal was to replace her network television with a constantly connected, self-updating message streaming service composed primarily of photos of tacos.

00:30:31

Here's how it works: I’m going to start with the blue arrow on the bottom left where it says 'phone'; that’s me. I'm going to send an MMS to the Twilio phone number I bought from Twilio for a dollar. Twilio will receive that bundle of MMS data and restructure it as an HTTP POST, which it will send to my web server — Hello Gmom. That’s the second marshmallow blob running in DigitalOcean's cloud, on one of their itty-bitty droplets. Once it gets that post, it will restructure it into a JSON blob because transforming data formats is what I do. It streams it over a WebSocket to that Pi Zero, which I duct-taped to the back of her TV, and it shows her the text.

00:31:34

Since it's a WebSocket, it enables two-way communication, so I can send a little note back to the web server. The server will relay that back to Twilio, which sends a confirmation message back to my phone, letting me know Barbara got my text. It’s just like real life! Here is what it looks like. This is the screen in her room; I apologize for the dark image. This handsome couple on the left is Bren and me at an arcade in Oregon.

00:32:20

Bren snapped this photo with her phone. We went to an arcade, hit send, and it showed up in her room. The second video captures Barbara being part of our conversations like anyone else. This is just the iOS messages app; there's nothing special about this. I'm going to type her a note reading 'Hi Gmom!' at Seagull, which is a Linux conference in Seattle where I gave this talk last month. I’ll hit send, and shortly after, I receive a '200 OK' because I'm a developer and think in HTTP status codes.

00:33:05

A few seconds later, there's the text. There are a couple of aspects worth mentioning. It’s important to note there was no photo in that text; it was an SMS versus an MMS, so the system knew how to handle both. In the absence of an attached photo, it showed a picture of me, giving Barbara something to hold on to about who was talking to her. I read a lot about typography and looked at various approaches to make things more readable for her. This example features a free font called Charter, created around the same time as Helvetica, known for its high readability.

00:33:53

Bren also conducted a terrific study where she created materials in different type sizes and held them around the room for Barbara to discuss what she could see. This helped us adjust the interface according to Barbara's capabilities. A few other interesting aspects of the system included employing a responsive layout, not because it would be viewed on different devices, but due to the various shapes of the incoming MMS. You can take tall pictures, wide pictures, and I was known to take square pictures.

00:34:36

I needed to build a system that could handle displaying those, so I leaned on what I knew about responsive design to accomplish this. The system had a great feature to reject random inputs; if someone got Barbara's phone number, they couldn’t send her malicious messages. There was an approved list managed on both the Twilio level and the web server level, as I anticipated that some people could be malicious and know how to format a post request. All of this was checked before messages were streamed over the WebSocket.

00:35:23

WebSockets are impressive! They might be displaced by Server-Sent Events, but I hope they don't disappear. Especially in Rails 5, ActionCable made it so approachable for building with WebSockets. I utilized a vanilla JavaScript object at the front that responded to these messages and knew how to queue them. I also learned how to write basic HTTP configurations and ran into challenges with creating my own SSL certificates using Let's Encrypt. Their documentation was helpful.

00:36:10

The system worked well enough, with my client connection being that single one to Barbara. The WebSocket would break if her DHCP lease expired. To fix that, I wrote a cron job to reboot the Pi once a day, ensuring that she always had a fresh lease. But the most significant outcome was that I had customized the interface according to her capabilities; it worked.

00:37:02

This little system from Twilio, a phone number, and about 50 lines of JavaScript made things better for Barbara and for us. It kept her in the forefront of our thoughts, giving us a way to feel connected that we didn't have before. Whenever we thought of her, maybe it was something cute on the bus or just stress at work, Bren or I could send her something, and we would receive a '200 OK' in return, which felt like we made her day a little bit better.

00:37:57

Though this is probably confirmation bias, I believe her cognition improved after receiving the device. That was her Christmas gift last year, which means she got it in January since it's software. She was excited! It took some time for us to demonstrate how to use it. The first photo we took was a selfie, sending it to her, saying 'Hi Grandma! We love you!' When that photo appeared on her screen, the look on her face was sheer joy. In her pre-stroke life, she loved little notes. She used to put a note in Bren's lunchbox; she’d send small tokens when she was thinking about someone.

00:38:52

This rekindling of connection to that past was far better than network television. So, let’s wrap up. In May of this year, Barbara suffered another series of strokes. We were with her both when the stroke occurred and when she passed about a week later. She left behind a legacy of determination, kindness, and grit — all traits that her granddaughter embodies. Now that she’s gone, I’m unsure what to do with this project. Obviously, I’ve written a talk about it, but it's obsolete; like many of the other things I've made, it’s deprecated.

00:39:51

Yet it's still the best thing I've ever shipped in 15 years of professionally creating software; it’s been my best work. I'm hoping that maybe, just maybe, I can encourage you to do something similar. I have a few closing thoughts: right now, I guarantee you someone you love has a problem you can help with. Maybe you can’t solve it — perhaps it can't be fixed — but it can definitely be soothed. You can make it better. We are uniquely positioned in time and space to do something about it. Some of us will undoubtedly solve huge population-threatening, world-changing problems.

00:40:40

Most of us will create significant financial value for others' lives; however, not enough of us will take a step back and build small things that improve life for the people we love. I want you to remember that not everything needs to be a product. In fact, I don't think most things should be a product. There is no ethical consumption under late-stage capitalism. I love that I get to stand on a stage and say that, but we must also eat.

00:41:28

That said, not everything needs to be productized. Worry less about whether your idea, side project, or little love letter can be transformed into a product. I was surprised I couldn’t find anything on the market that did this. I found some Wi-Fi-enabled photo frames, but nothing that provided that sense of connection we wanted, nothing that allowed us to remotely alter the content on the screen. So, I had to build it. When I discuss this project with people, a common response is usually, 'You should kickstart that!' But really, kickstart what? Being nice to your grandmother? You can’t kickstart the act of love.

00:42:16

If I had thought about creating a product first, I would never have shipped anything. And if I had shipped something, it wouldn’t have been what she needed; it wouldn't have been tailored for her. We are all individuals, and not everything needs to be generic. The nursing staff at Grandma's home were amazing, and we could learn a lot from the people doing that work. They give so much of themselves to safeguard whatever humanity and agency their residents have.

00:42:58

I didn't know how to weave that into my talk, but it's important to note they were a constant presence in Barbara's life, supporting her when we couldn’t be there. I'm extremely grateful for that. At some point, most of us will face this kind of adversity; perhaps it'll be us who has our agency removed, or perhaps it will be someone we love. But we will all need someone to step in for us, and I encourage you to do whatever you can to provide relevance and dignity to the people in your life. Thank you.

00:43:50

Oh, and everything's open-source, by the way! This includes the Nginx config and all the articles I used about working with SSL and making DigitalOcean work with all this.

00:44:08

This is a great question: what was on the screen between texts? I forgot to mention this: we maintained a queue of messages that would cycle through, and we conducted a lot of UX studies on what display rates were appropriate and how many messages should be in the queue. While it’s dark to say, some of Barbara's memory impairments worked in our favor because messages were often new to her, especially if she had napped or slept — a message might feel fresh again.

00:44:56

We originally settled on about 40 messages, typically representing a week's worth, displayed at about a minute each. Technically, could it support group texts? Yes, but I never figured out a good way to display a threaded message, given that the device had to be fairly passive in its consumption, and we wanted to avoid overwhelming it with information. I would love to solve that problem, but I don’t yet know who else this project is for. Thank you so much!