00:00:16.070

Hi! So there's a piano back here. Does anyone know how to play the piano? Because I need someone to play me onto the stage. We're going to do that whole thing over again. No? Okay.

00:00:25.680

Hi there! Thank you for coming. The sign reads responsibility, Nuremberg, and Krishna, and you're in the right place if that is what you wanted to see. But I changed the title of the talk, as I usually do right before I give it.

00:00:35.370

As Jamie mentioned in my previous talk on software ethics, I shared a story about how I built software to find Wi-Fi hotspots by looking at how their signal strength changed as my phone moved around. What I didn’t know was that the real use for the software was not to find Wi-Fi hotspots, but rather to help people — its purpose was to help soldiers with guns find people by tracking signals broadcast by their phones. I built this at the same time that we found out that the military had been spying on Americans in America with drones.

00:01:02.149

Even if I was okay with helping them find people, which I wasn’t in the first place, I was definitely not okay with them helping find U.S. citizens in the country where I live. Now, I don’t know if anyone here has ever used this software. I was an intern without a security clearance, and so in all likelihood, everything I was working on was just put into a drawer somewhere and forgotten about. But the chance that it helped to murder people weighs on me heavily, and it probably always will.

00:01:32.180

Today, though, I want to talk to you about someone who did something far worse and about his struggle for the remainder of his life to mitigate the negative consequences of his actions. I want to talk to you about the father of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

00:01:58.430

Oppenheimer's early life helped shape much of his work on the Manhattan Project, the codename for the U.S. program to develop the technology for the atomic bomb in the early and mid-1940s. His early education took place at the Ethical Culture Society, a movement founded by a rabbi who believed in the need for a religion without the trappings of ritual and creed, uniting all mankind in moral and social action.

00:02:13.650

Oppenheimer’s father had moved to America penniless, with no higher education and without speaking English. He got a job at a textiles company and worked his way up to an executive role over a decade. Now he was a wealthy man living in Manhattan with a sizable art collection. He had been a member of the Ethical Culture Society for many years and was involved with the school as well.

00:02:43.470

The younger Oppenheimer was a versatile scholar. He was interested in English and French literature, and especially in mineralogy. He wrote to various mineralogists as a young boy, unaware of his age. One of these correspondents nominated Robert for a membership and to give a lecture for a mineralogical club in New York.

00:03:01.049

Robert was terrified to give a presentation to adults. I can relate! He begged his father to explain that they had invited a 12-year-old. His father was greatly amused and encouraged his son to accept the honor. Robert showed up, startling the audience of geologists, who laughed out loud. They placed a wooden box below the podium so that he could stand and be seen. Nonetheless, he read his prepared remarks and received a hearty round of applause.

00:03:22.210

This interest in and adeptness at a broad range of topics would be a consistent theme throughout Oppenheimer's life. He would read and write poetry, study languages, philosophy, and religions. Oppenheimer was a genius when it came to understanding theories and concepts, but he was a clumsy and inept scientist when it came to the meticulous work involved in laboratory physics.

00:03:59.999

In his postgraduate studies at Cambridge in 1929, Oppenheimer had a severe mental break. His good friend from the Ethical Culture School, Francis Ferguson, noted in his journal that Oppenheimer had a first-class case of depression. While there’s no reliable account of this, Robert claimed to have left a poisoned apple on the desk of his tutor at Cambridge, Patrick Blackett, who is here on the screen.

00:04:13.409

Though Oppenheimer liked Blackett, his tutor was a hands-on experimental physicist, who was everything that Robert wasn’t. He pressured Robert to become better by doing the things that he wasn’t very good at. This caused all of Oppenheimer's already intense anxiety to increase, culminating in Robert poisoning this apple and leaving it on the physicist’s desk.

00:04:48.950

Whether Blackett detected the poison or if it was more of a laxative, or just something to make him sick, maybe even the apple was something Robert invented in his mind — we don't really know. But we do know that Blackett was not actually injured, and despite that, it was a very serious matter. It was grounds for expulsion from Cambridge. His parents, who were visiting due to Robert’s emotional state, lobbied the university not to press charges or expel him on the condition that Robert see a psychiatrist.

00:05:52.720

Robert was later diagnosed with dementia praecox, which is an archaic term for symptoms we now know as schizophrenia — bouts of depression and self-destructive tendencies followed Robert for the rest of his life, though nothing quite as serious as this one. He said in a letter to his brother Frank Oppenheimer years later that, 'I can't think that it would be terrible of me to say, and it is occasionally true, that I need physics more than friends.' Until about 1934, after his postgraduate studies, Robert became a professor, splitting time at Berkeley and Caltech.

00:06:03.669

Oppenheimer displayed little interest in politics until Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the previous year began to intrude on Robert's carefully cultivated self-image of an unenrolled, withdrawn, aesthetical person who didn’t know what was going on. In the spring of 1934, Oppenheimer agreed to earmark 3% of his annual salary, amounting to roughly $100 for two years, to support German physicists attempting to immigrate from Germany to the United States.

00:06:35.320

He would later invite some of his students to attend a Longshoremen's rally. They sat high in a balcony and recalled that they were caught up in the enthusiasm shouting, 'Strike! Strike! Strike!'. Oppenheimer met a woman named Jean Tatlock in the spring of 1936. She was a complicated woman, certain to hold the interest of a physicist with an acute sense of the psychological.

00:07:07.830

She would also become Oppenheimer's truest love, as a friend would later describe her. She would continue with an affair with him even after he married his wife years later. It’s only natural that Jean's activism and social conscience awakened a sense of social responsibility in Robert, a sense that had been often discussed at the Ethical Culture School.

00:07:30.430

It was Jean who opened the door for Robert into the world of politics. Over the next few years, Oppenheimer would become progressively more interested in left-leaning politics and became especially enamored with communist ideas coming out of the USSR. He would donate to causes such as the Spanish revolution in cash and through communist front organizations. He continued his involvement with unions, including joining the teachers' union, and attended and hosted gatherings where politics were discussed.

00:08:13.210

Though he would later completely cut off these associations involuntarily before joining the Manhattan Project, he was never a formal, dues-paying member of the Communist Party. These associations and his status as a fellow traveler would come up again and again as his enemies tried to strip him of his political power, preventing him from being involved with the bomb projects.

00:09:10.400

His communist leanings in the '30s did not stop Oppenheimer from wanting to help his country with his knowledge of physics when the war effort required it. He told his friend Arthur Compton, 'I'm cutting off every communist connection, for if I don't the government will find it difficult to use me, and I don't want to let anything interfere with my usefulness to the nation.' By September 1942, Oppenheimer's name was being floated as a candidate to direct a secret weapons lab that would coordinate the efforts around the country on the development of an atomic bomb.

00:09:51.570

After meeting General Leslie Groves, the military commander of the Manhattan Engineer District, better known as the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer left Groves with the impression of a real genius who knew about everything. Oppenheimer was the first scientist Groves met who grasped that building an atomic bomb required finding practical solutions to a variety of cross-disciplinary problems.

00:11:07.880

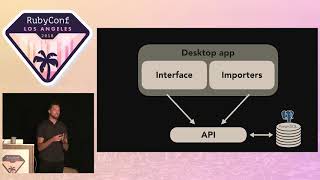

He proposed centralizing the efforts at Princeton, Chicago, and Berkeley into one location where they could begin to address the chemical, metallurgical, engineering, and ordnance problems that had so far received no consideration at all. Groves proposed Oppenheimer’s directorship of the Manhattan Project, and immediately after his appointment, Oppenheimer began to court key figures in the scientific community.

00:11:47.600

In addition to recruiting many of his graduate students, he recruited notable scientists such as Hans Bethe, David Bohm, and Richard Feynman. But at the same time, he faced his close friends turning him down on ethical grounds. One of his closest friends, Isidore Rabi, later said, 'I was strongly opposed to the bombing ever since 1931 when I saw those pictures of the Japanese bombing that suburb of Shanghai. If you drop a bomb, it falls on the just and unjust — there’s no escape from it.'

00:12:32.600

During the war in Germany, we certainly helped develop devices for bombing, but this was a real enemy in a serious matter. However, the atomic bombing just carried this principle one step further, and I didn’t like it then, and I don’t like it now. Something similar happened this past summer when Salesforce and Google employees separately wrote letters to their respective companies to re-examine their relationships with Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Defense.

00:14:29.800

These employees stood up for what they felt was ethical, but they worked within the system to try and make a change, and it worked. Oppenheimer was motivated by American patriotism, fear of Germany's treatment of the Jews, fear of Germany's own atomic bomb program, and by the interesting scientific and logistics problems that went into building an atomic bomb.

00:14:48.140

He worked for roughly three years as director of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, effectively acting as a liaison between the military and the scientists on the project up until the point where the first Trinity test took place, which was the first atomic explosion. Oppenheimer is perhaps most famous for what he is reported to have said immediately after the explosion: 'I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.'

00:15:34.440

Some